Written by Mark Millar

Art by Frank Quitely

Published by Image Comics

You never know what you're going to get with Mark Millar comics. Actually, that's not true. You can usually guarantee that you'll get something "edgy", characters speaking "cool" dialogue, some concepts that seem new and exciting until you realize that they're mostly just tropes recycled from other, better creators and given the ol' modern Millar take (preferably pared down to something that will be easily adapted into a movie), and, if you're lucky, some pretty good superhero action. So why bother with his latest tiresome thing? In this case, his co-creator makes it worth a look. You can always expect Frank Quitely to deliver great artwork, and this is no exception. He makes the action and character interplay here work really well, enough so that you almost forget about the empty shell of a story that Millar has delivered.

Here's the thing with Millar: he tries to seem relevant, or at least new, when he's creating these takes on superheroes, but there's never anything going on below the surface. In this case, he seems to be going for a generational story, possibly commenting on where society is now versus where it was when superheroes were first created. But he doesn't actually have anything to say about either generation or time period; they're just the latest mold into which he can pour a violent superheroic conflict.

I probably don't need to get into specifics, since what I just described is something that Millar has done time and again, but let's look at how this story doesn't hold up. The comic kicks off in 1932 with a small group of friends going on an expedition in search of a mysterious island in the Pacific Ocean that their leader saw in a vision. We find out that after they found the island, they were given superpowers (how they got them is treated as a big secret, but later we find out that it was just aliens who apparently wanted to make America great again) and came back to change the world, pulling the United States out of the Great Depression and ushering in several decades of heroism. Fast forward to 2013, and now their kids are living as entitled celebrities, lacking the moral character of the earlier generation and feeling like there's nothing left for them to do, since their parents have already defeated all the villains.

So, there's at least an idea there, with a conflict between generations (although why did it take the heroes more than 50 years to have kids? Shouldn't there be at least one more generation there in between the original heroes and the ones that were presumably born in the 1990s?), maybe something about Millenials being left adrift and older generations not understanding why their kids don't share their values, not noticing how the world is crumbling around them? Unfortunately, the kids don't actually have enough drive to actually engage their parents in a battle of wills, so the main plot conflict ends up being between the Utopian, the leader of the heroes, and his brother Walter (who I guess is called Brainwave, but I don't think that ever comes up in this volume of the series), who has felt like the Utopian has been holding him back all these years, insisting that the heroes only fight evil and not get involved in politics (this begs the question of how exactly they pulled the US out of the depression in the first place. Just by leading by moral example and encouraging people to work harder?). So, Walter convinces the Utopian's son Brandon that his father has been holding him back and it's time for him to lead. For some reason, all the other heroes (only one or two of which actually get names or speaking parts; where did these dozens of other heroes, and the villains they fought, get their powers, anyway?) not only take Walter's side, they get on board with the vicious murder of the Utopian, his wife, and his daughter. But that can't be the end of things, so the daughter, Chloe, escapes (not through any demonstration of agency of her own; no, she gets rescued by her boyfriend, the son of a supervillain), going into hiding and raising her son in the increasingly dystopian world that Walter and Brandon soon create. We catch up with them ten years later, with the kid being raised to believe in heroic ideals and secretly using his powers to fight for good, until, of course, he gets discovered, his family is exposed, and they have to stand up against the forces of oppression.

But that will have to be a story for another volume, since this is just the first installment of a series that may or may not ever be completed in comics form (it will probably get turned into a movie first). For now, all we have is this volume, which has precious little going on below the surface. If we're meant to buy into this world at all, we should get a sense that heroic conflicts have been going on for decades, but there's nothing to suggest how the existence of these amazing people has changed the world, and other than a few mentions of fights against villains, we have no idea what they've been up to for the past 80 years. We should be able to tell that the tension between Walter and his brother has been simmering for so long that it has finally come to a boiling point, but there's no sense of shared history between them, there's just arguing meant to advance the plot.

And what of the actual feints toward politics and relevance? The little we see of Walter's plan to fix the US economy (before the Utopian shuts him down for no discernable reason) is basically gibberish:

Really, Millar has no real idea of how superheroes would realistically affect the world outside of how they affect the plot. After we jump ten years into the future, we see that Walter and Brandon's plans to make everything better have failed, turning the world into an Orwellian nightmare in which any remaining heroes or villains are hunted down and presumably executed. But why did their plan fail? In what way did it make things worse instead of better? Why did they turn to rigid control of the populace rather than promoting personal freedom? I could probably come up with some answers to those questions, but Millar doesn't even bother; he needed an evil empire for his remaining heroes to fight against, and even though characters occasionally speak lines of dialogue that makes this all sound relevant, it's really all just a poorly-thought-out plot being hammered into place.

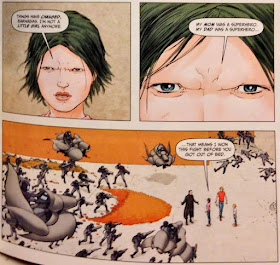

So, empty as this comic is, is it worth reading at all? Well, Frank Quitely certainly does his best to paint as pretty a picture as he can on top of this fragile eggshell, and if you're willing to be generous enough to Millar to accept that there's absolutely nothing going on below the surface of this superhero fight delivery device, I suppose you'll be able to enjoy it. Quitely sells a sense of scale in superhero comics like few other artists, so it's fun to watch him detail the large battles and amazing feats the characters get up to (although there are fewer of these than there really should be; like I said, there is no sense of what the world is actually like with all these costumed characters flying around). There's little sense of personality in anyone beyond the six or seven main characters, but Quitely does what he can to fill panels with other people, interesting costume designs, and nice-looking settings. And there's at least one cool superheroic fight scene of the type that Millar excels at, with characters using their powers in interesting and exciting ways and the day being won while badass proclamations are uttered:

If more of the book was like that, helping us understand why we should care about what happens to these people rather than just assuming that their lives are important because the text says so, maybe there would be something here. And who knows, maybe Millar will take the time to detail more of what happened in the characters' pasts and explore what must be a backstory that took place during the huge time gaps of this volume (he has also done a prequel series called Jupiter's Circle, illustrated by Wilfredo Torres). But somehow, I doubt it, and I'll be surprised if there's ever any suggestion that there was some actual thought put into this other than how much money it can make when it gets turned into a movie. So, when does volume 2 come out?